Human data machines

Many would agree, the idea of sampling Gushers, snacking on Nature Valley granola bars and trying out the newest flavor of Yoplait yogurt sounds like the kind of thing you’d do for free.

But as it turns out, the job of a food taster is more technical than it sounds.

General Mills employs food tasters who sample our products for a living, and these trained professionals provide data about our food that no machine could ever replicate.

According to Terese Tamminen, senior scientist in our Innovation, Technology and Quality group, these “human data machines” provide analysis on our products that is essential to understanding how consumers experience our food.

And it plays a key role in achieving our mission to Serve the World by Making Food The World Loves.

“Eating is a very complex experience. Your taste, your salivary flow, your teeth – all of that plays a role,” says Tamminen. “Our panelists take references from scales and they translate them to flavor and texture to give us ratings on what the experience is like while eating and into the aftertaste.”

It goes far beyond a simple matter of preference; these food tasting panelists have such a finely-tuned ability to taste that they can tease out even very mild flavors in products, or capture the difference between small changes to a product’s recipe.

And our food tasters play an integral role in helping General Mills evaluate our products and understand precisely what consumers experience when they eat our foods.

Becoming a General Mills food taster

To get equipped for this kind of analysis, food tasters go through a rigorous training to develop the skills and acumen needed.

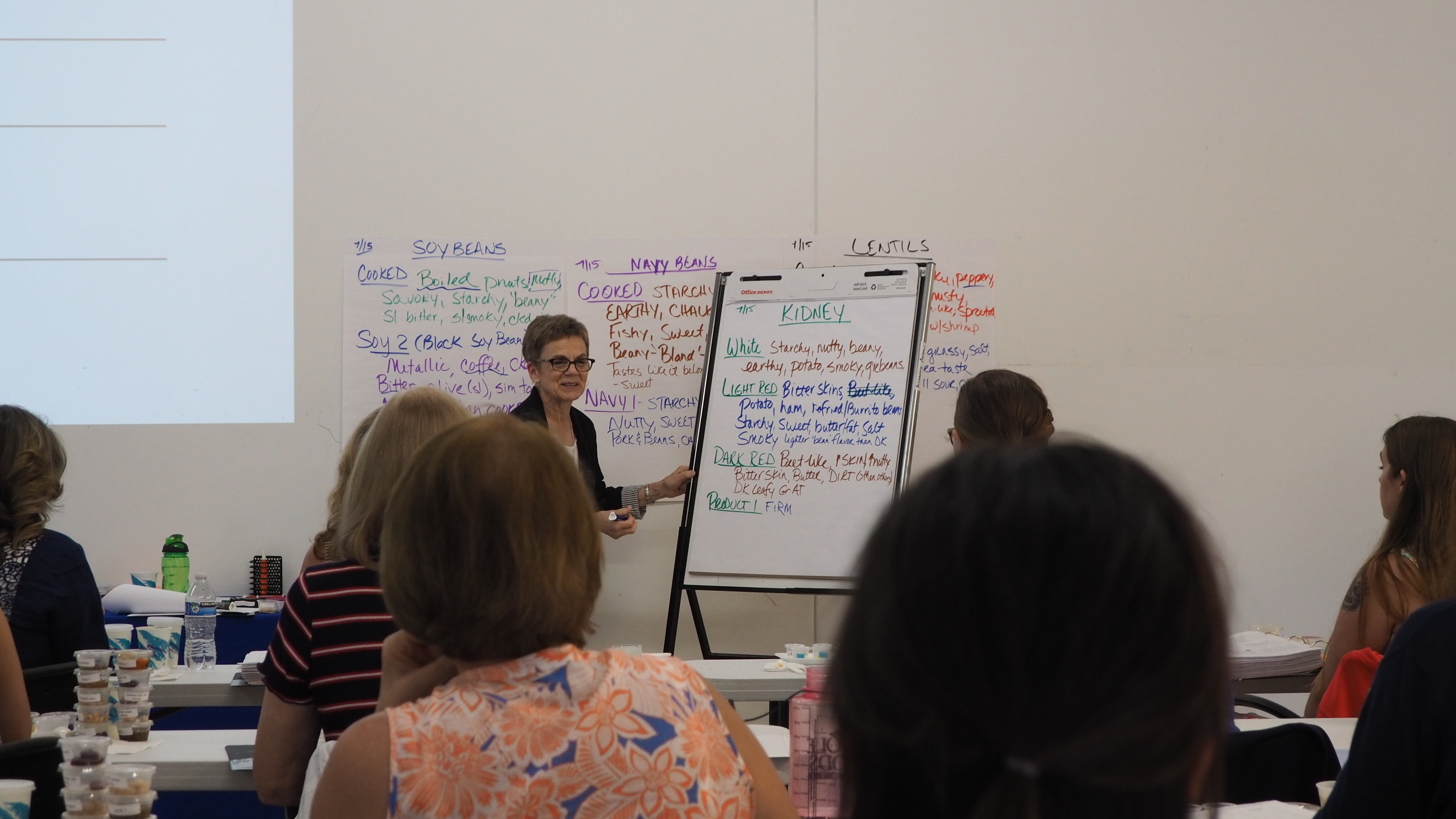

This summer, Sue Tomlinson, descriptive analysis panel leader, has been training a new group of food panelists.

These panelists-in-training were thoroughly screened for acuity, ability to estimate magnitude of different intensities and their aptitude to work on teams. Tomlinson says these skills are essential to being successful as a food taster.

Those that make it through application and screening, start learning the essentials.

“They’ll learn the spectrum scale, they’ll learn texture, attributes, definitions, techniques. But knowing yourself is also key,” says Tomlinson.

Ellen Fudge, one of our panelists in training, says the experience has taught her a whole new way of understanding taste, beyond preference.

“For us, it’s not as simple as ‘This tastes like oregano.’ We look at what oregano tastes like, what complex it is made out of, and really break down more complex flavorings into their individual components,” says Fudge.

On a normal training day, Fudge says they work on scaling basic tastes and learning universal scales.

They learn how to rate flavors, and how to describe those ratings. What’s the difference between a grape flavor of five, and a grape flavor of seven? After several hours of tasting and analysis, they learn how to fine-tune their senses to tell the difference between even subtle variations in flavor.

Fudge says she has a new appreciation for flavor nuances in her personal life, after diving deeper into this kind of taste analysis.

“It changes how I cook, what food I order at restaurants – it makes me think about what flavors I really do want to bring out, and thus the ingredients that go into it,” says Fudge. Fudge also sees an important connection between her work as a food taster and General Mills’ commitment to being a consumer-first company.

“It’s putting every single item that comes out of General Mills to a very rigorous test, to make sure it aligns with what they want it to be and what it has been in the past,” added Fudge. “It’s another piece of the puzzle to making products that are regulatable and able to be enjoyed by everyone.”